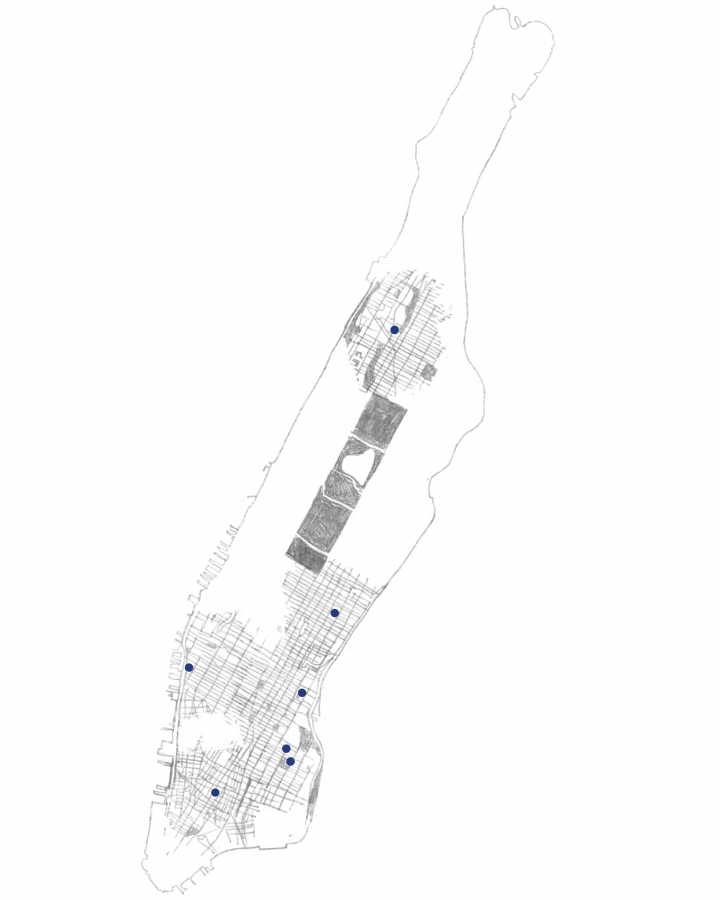

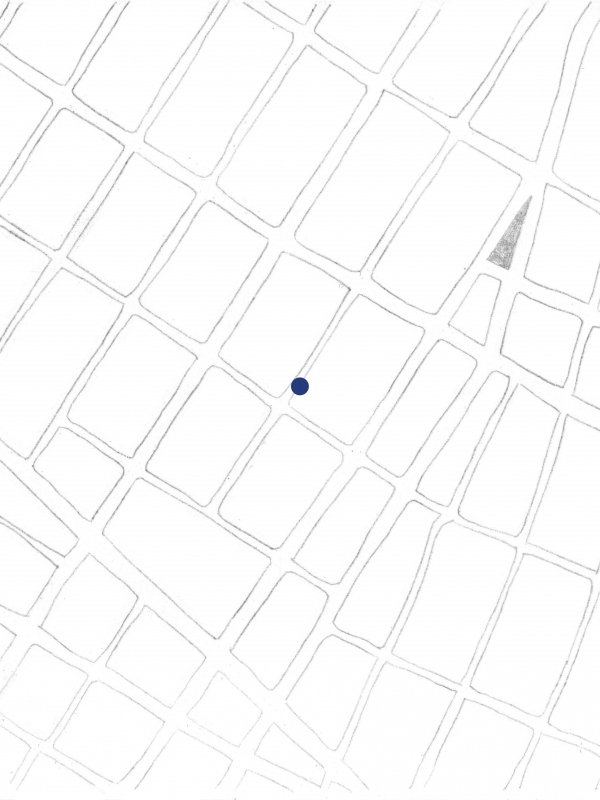

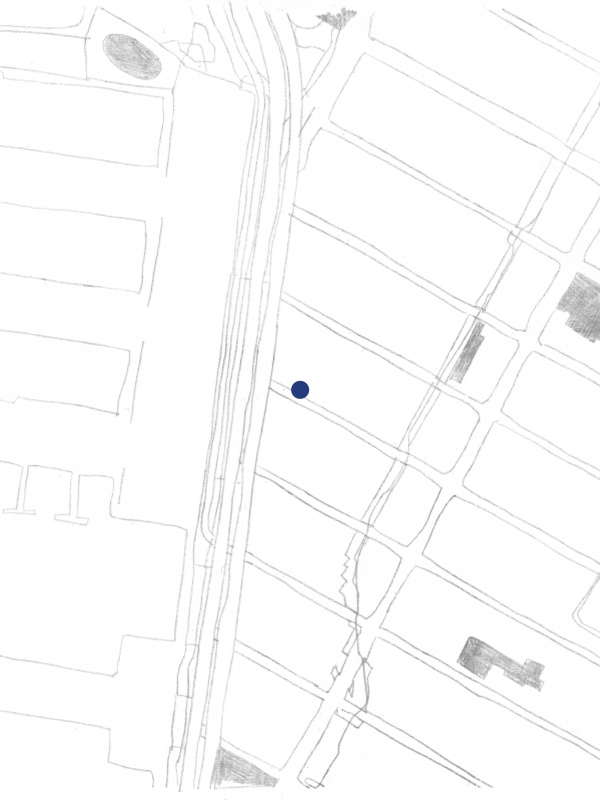

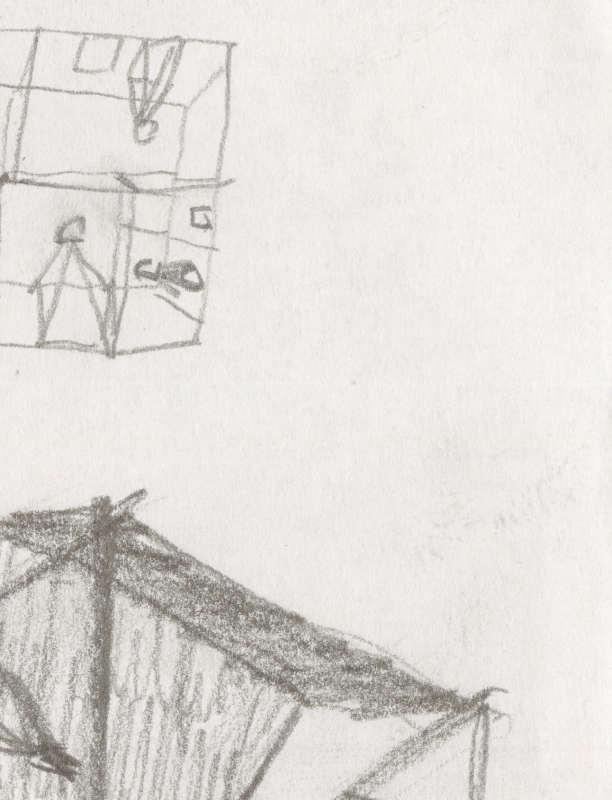

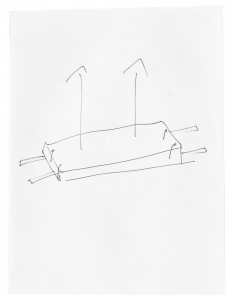

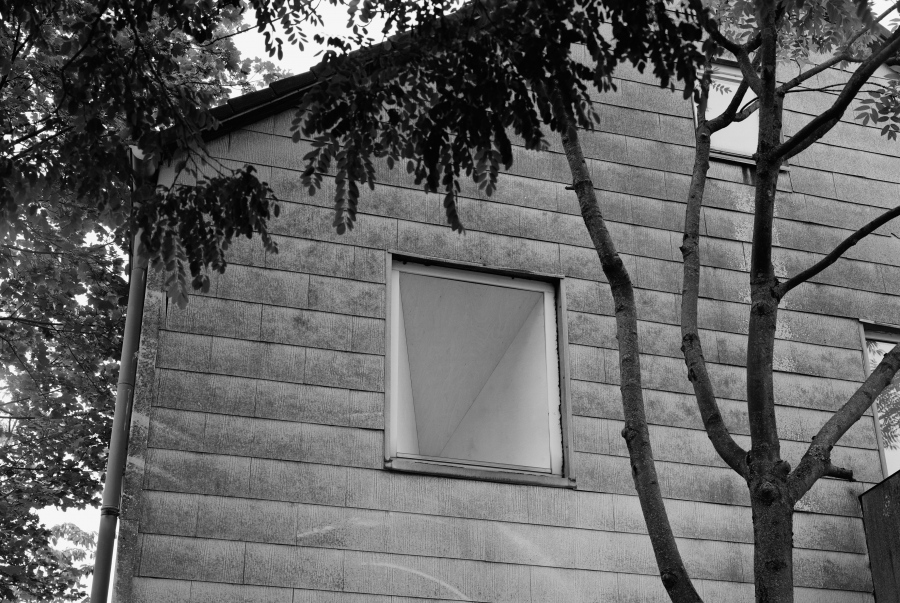

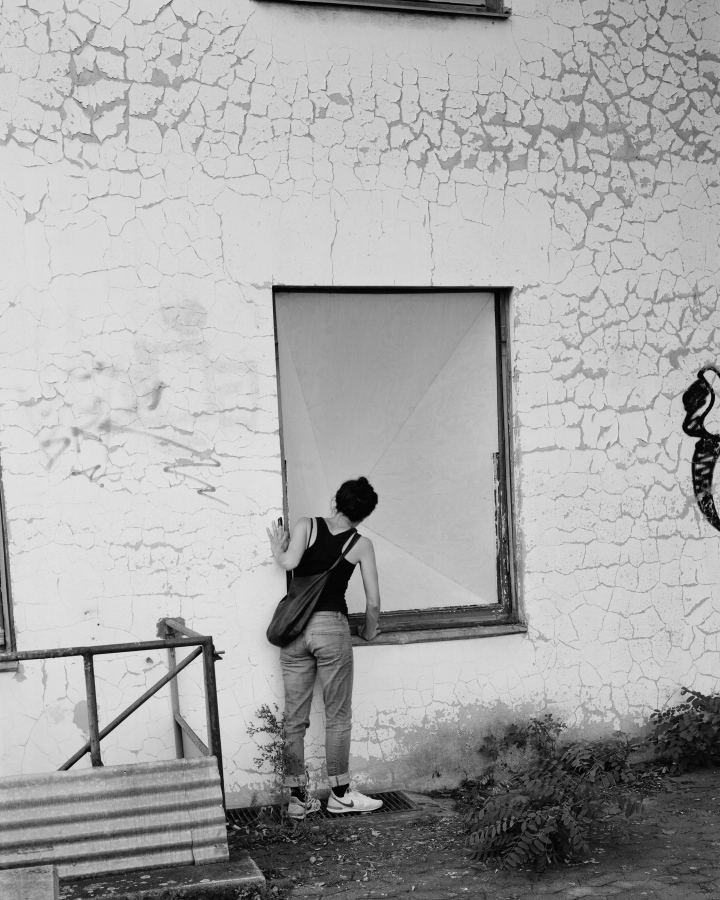

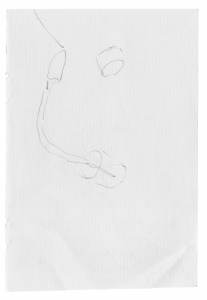

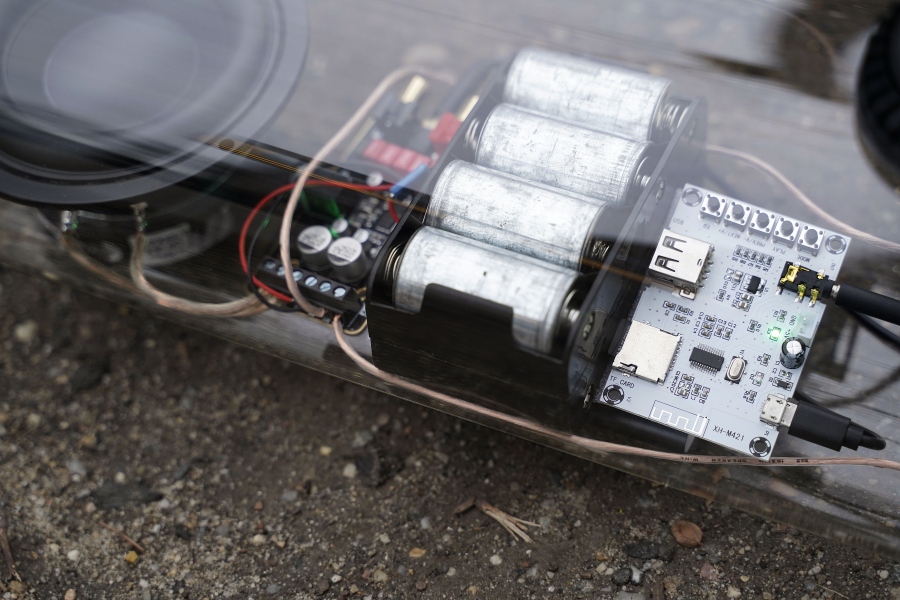

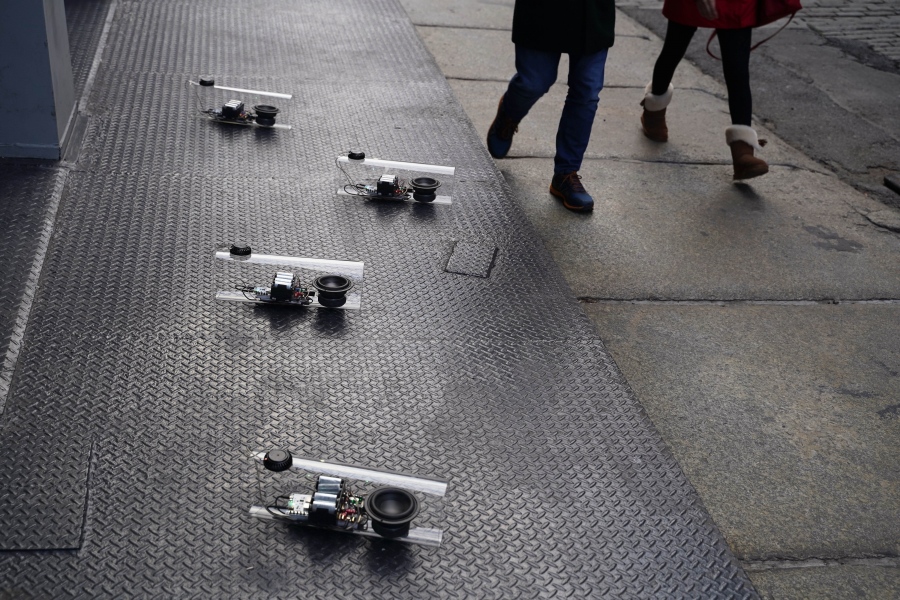

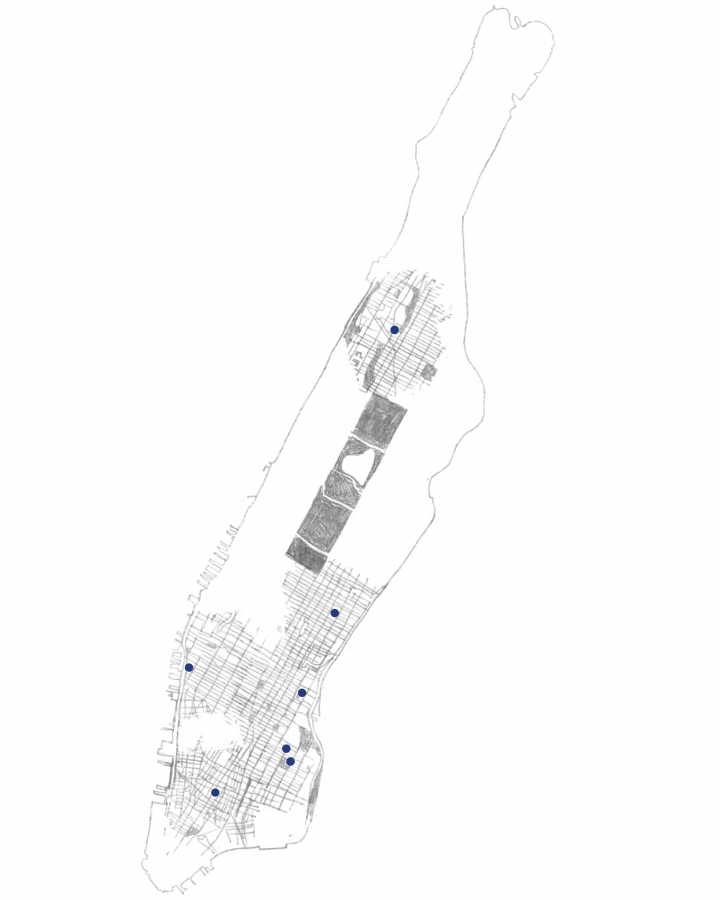

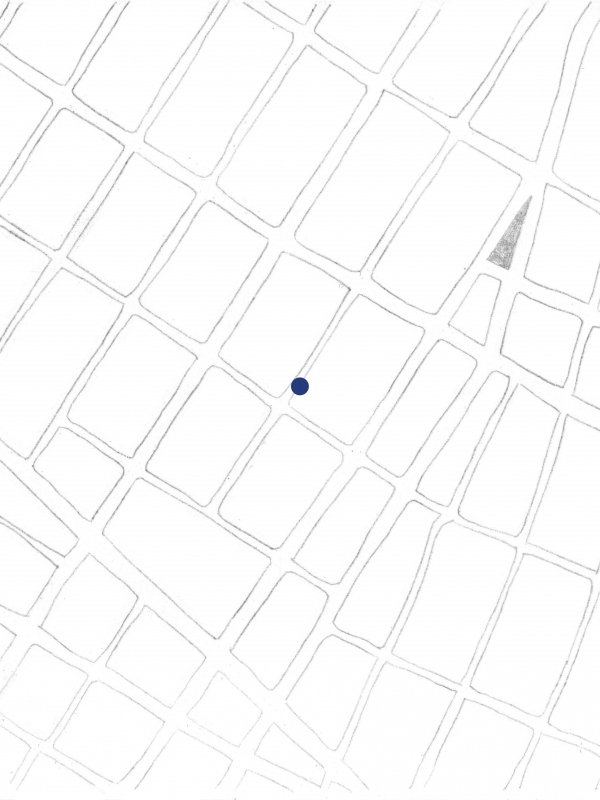

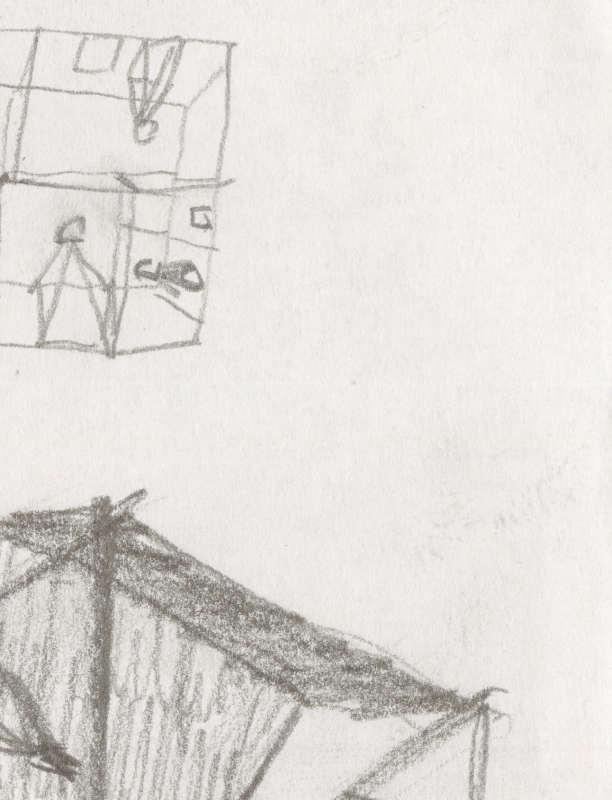

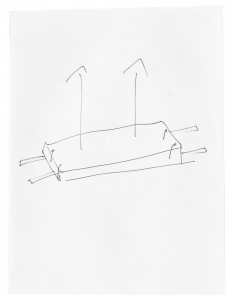

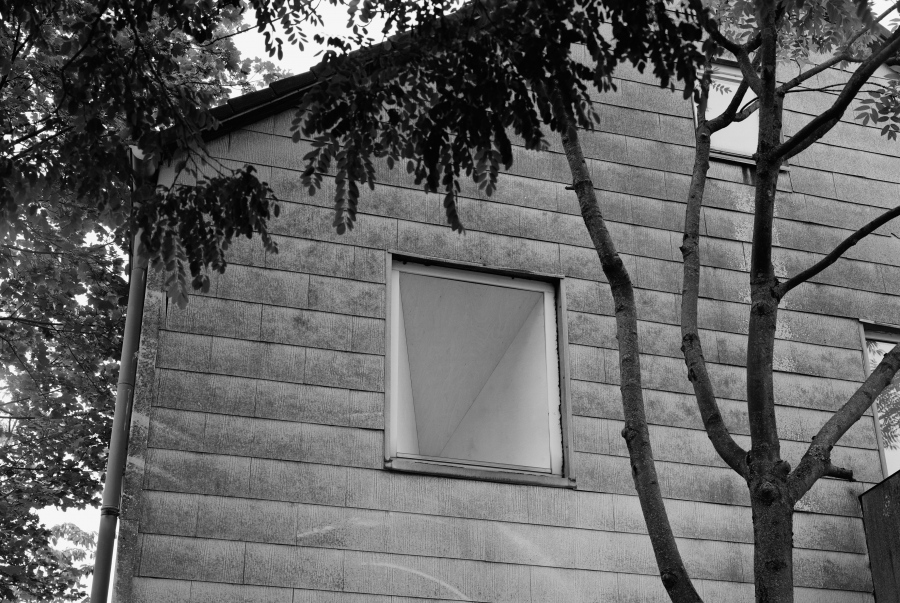

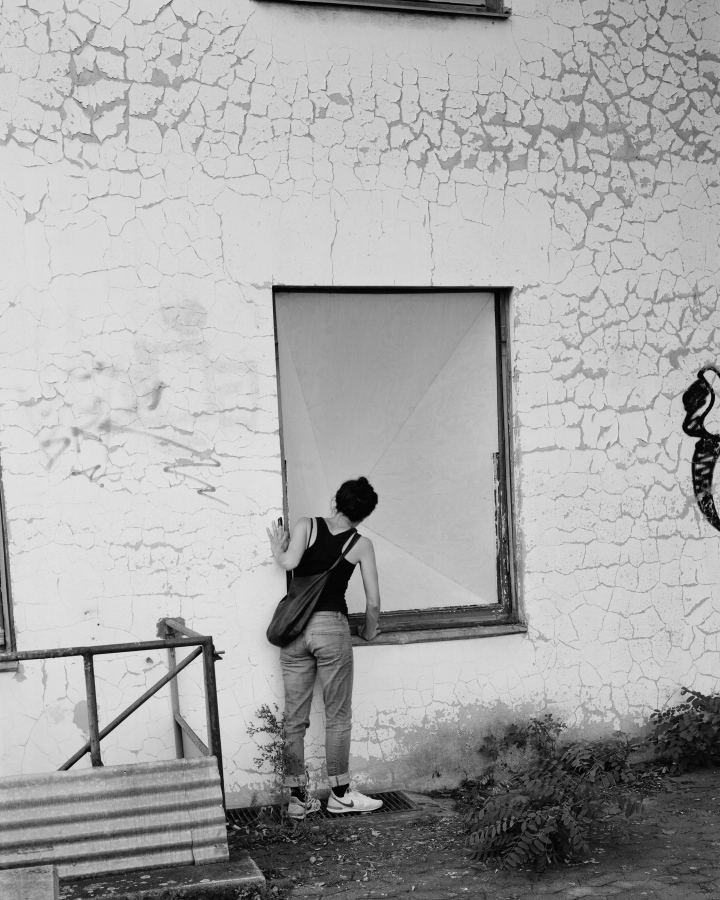

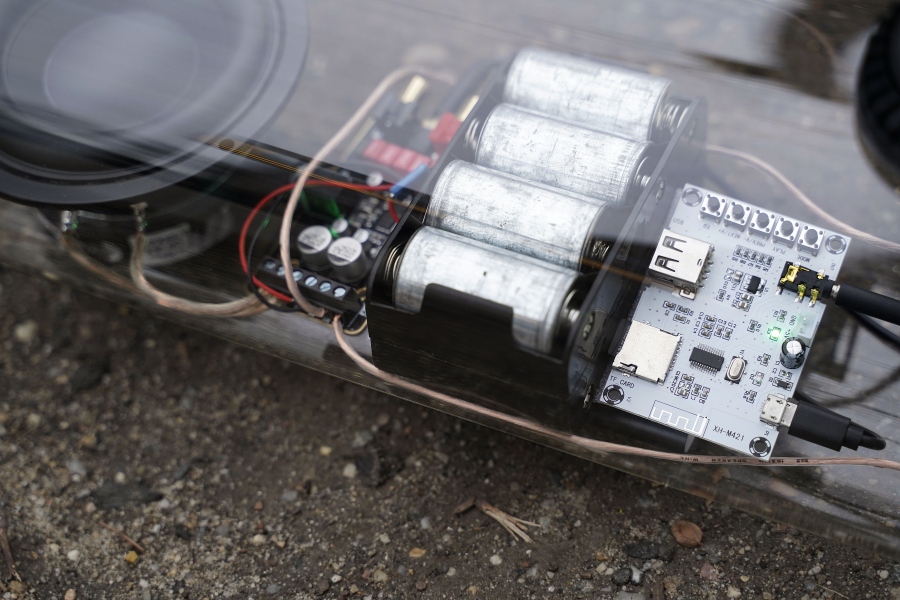

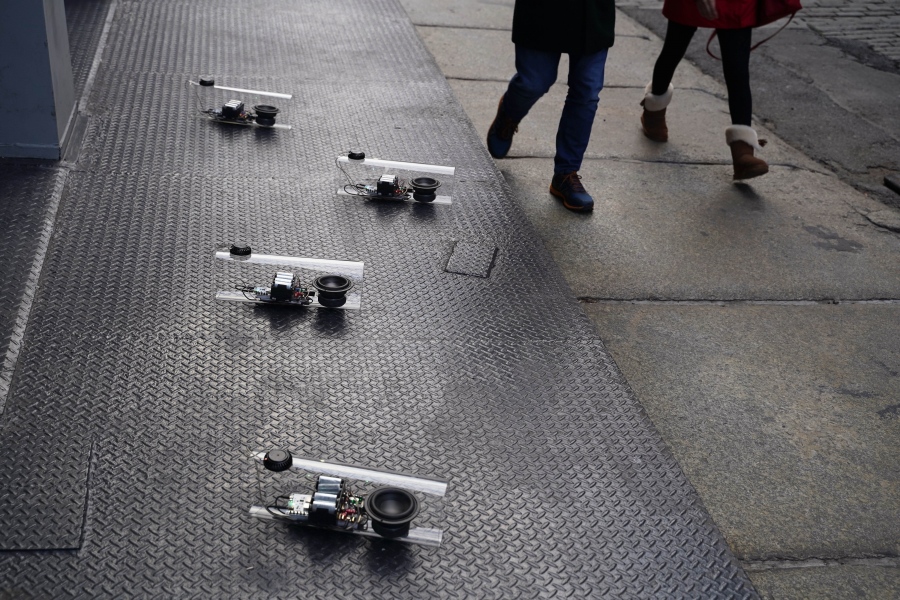

In situ at various locations in Manhattan, New York, USA:

Built with Berta.me

Copyright Fritjof Mangerich 2020, all rights reserved.